Welcome back to Reading the Weird, in which we get girl cooties all over weird fiction, cosmic horror, and Lovecraftiana—from its historical roots through its most recent branches.

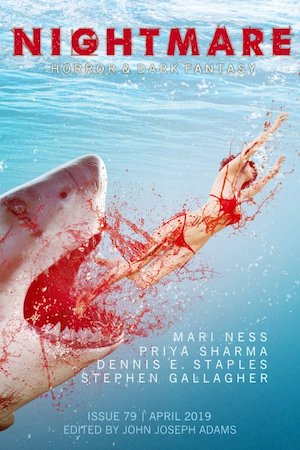

This week, we cover Mari Ness’s “The Girl and the House,” first published in the April 2019 issue of Nightmare Magazine. Spoilers ahead!

“She cannot—will not—become one of the women locked in the attic, or locked in the crypt.”

The girl comes to not just any house, but a mansion built from a ruined abbey or castle. It’s situated on sea-swept cliffs, or foggy moorland, or deep in a rugged forest, “a house of secrets, a house of ghosts and haunts.”

The girl is alone, with no one to call on for help: orphaned, any surviving relations indifferent, with few friends made at the orphanage or school. Still, she’s better off than the girls who are locked away or thrown into the streets. At this new house, she’ll be a governess, or companion, or distant relative, never a servant. Servants, she knows, never star in this kind of story, for all they’re uniquely positioned to hear gossip and explore the house while avoiding the rough-tongued cook below stairs. The girl must be neither quite family nor staff; her position with the man will be uncertain.

The house has a man, of course, its owner or heir, given to mysterious moods that render him of “endless fascination.” There must be at least one other man to provide a contrasting object of interest, happier and more stable, a joker perhaps. Beware: joking men often use charm to conceal “their thirst for blood.” She might be better off with the moody master, or with one of the women.

The girl doesn’t know whom to trust. She doesn’t really know which of the women are sane, which mad, and she discounts the maids who are more intelligent and observant than she gives them credit for. Some women are locked in attics or crypts. Some lock themselves in. Some don’t want to meet the girl. The girl cannot become one of the locked-up women, although the idea of being locked in a space all her own is tempting. She has a house to explore, people to save, and her attraction to the central male to resolve.

None of the other residents can help her, “beyond dropping mysterious hints over tea.” The tea tastes odd, but no one wants to antagonize the cook by mentioning this. Some residents tell ghost stories. Some bring up the many women the brooding man has known. The maids believe he broods because he’s known many women, but it could be vice versa. Any children in the house are adorable, but also troubled. The locked-away women say nothing, or nothing comprehensible.

The girl won’t take any of the residents on her explorations. The house has made them fearful, or else their blood has. Old families, and houses, are prone to such frailties. The brooding man would steer her away from his secrets. The cheerful man might be a murderer.

The girl’s arrival may convince the residents to host a party like those the house saw in the days before… before the unmentionable catastrophe occurred, so long ago even the locked-away women can’t remember it.

The house seems to the girl to tremble at the thought of the party. The girl knows she must conduct herself with care during it, both with the brooding man and the cheerful one who might be carrying daggers or poison. The brooding man may hire musicians to drown out the howling ghosts. Some may take this as a sign that he’s throwing off the house’s shadow at last. Naturally, though, the party ends with the discovery of a body. It’s topped by three silver bells, like the ones that appear every Thursday in the girl’s room.

She must use the bells to reveal the house’s secrets. The house itself is anxious for revelation. It’s waited a long time. It wants to live. The girl will uncover which cheerful man is the murderer. She will teach the children that monsters aren’t creatures only of their imaginations, or of the house. She will prove the locked-away women aren’t mad—they’ve just known too many monsters. Oh, and she’ll show that everyone, especially that corpse, should’ve paid more attention to the cook.

Only when all these things are done can she let her fingers sink into the walls, letting the house sink in turn into her skin. When she leaves—which she inevitably will—she’ll take the house and its residents with her. She’ll be haunted, but the house within her will be “a strong guard against loneliness—and monsters.”

She’ll also know it’s wise to pay attention to the cook!

Libronomicon: Suppose we overlook the curse, and hold a good old-fashioned party? What are the chances that a body will be found just when guests are sitting down to dinner? Surely that sort of thing only happens in books!

The Degenerate Dutch: In a house like this, charming men conceal a thirst for blood. You might be better off with the ones who want to lock you in the attic, assuming they’ll feed you there. Or with another woman, getting yourself into a different genre as swiftly as possible.

Madness Takes Its Toll: The house has women, some of them mad. Or perhaps they’re all sane, responding sensibly to the madness of the house and its monsters.

Anne’s Commentary

In the Nightmare Magazine author spotlight appended to “The Girl and the Book,” Mari Ness names the Gothic romances of Eleanor Hibbert (aka Victoria Holt) as a virtual compendium for the cliches alluded to in her short story. I grew up among Victoria Holt books, which regularly entered our family library via book club hardcovers and paperbacks exchanged among my mother’s friends until they disintegrated in my grubby and none-too-gentle hands. I remember the covers best, as so many featured compelling images of girls running away from houses that loomed menacingly under storm-swept skies. Often the girls were clad in diaphanous nightgowns, making one worry they’d catch their deaths of the sniffles or at least ruin their hairdos. Here’s a fair representative of this pleasing artwork:

You can read up on the trope of Girls Running from Houses at Joan Aiken’s website, which essay includes more juicy examples of “fleeing female” covers.

At the oft-palpitating heart of the gothic romance are indeed the young woman and the house of mysteries she enters in hopes of a haven and new life. A man owns and is therefore a principal part of the house and one of its central mysteries, generally as to why he’s so damn moody all the time. Some speculate there’s a woman to blame, or women, like the ones locked in the attic or basement or at least sequestered in a sickroom. Or, if dead, the woman haunts the house in the form of her portrait or her hidden journals/correspondence or perhaps a child, legitimate or otherwise. It could be the moody man has vanished her alive (as in that attic) or even killed her; either way, if the heroine is to redeem this man with her love, he must be redeemable. That is, the woman or women must have been gravely at fault, the man more sinned against than sinning. If Mr. Moody is really a villain, the heroine must reject him for another man, probably one initially unassuming rather than too upbeat and charming. The cheerful charmers have something up their sleeves, like a dagger.

But Mr. Moody usually wins out. Why not—he’s the Bad Boy who’s Not Too Bad. Maybe he doesn’t have a Heart of Gold exactly, but a Heart of Silver is good enough. However tarnished, it’s a vital organ the heroine can polish up.

From way back in the days when Ann Radcliffe was queen of the Gothic novel, the genre’s tropes were well-worn enough to inspire ridicule. The best satire, however, springs from contempt tempered by love, and so it’s Jane Austen who takes the prize. Northanger Abbey abounds in the cliches rather lovingly flogged by Mari Ness. A girl (Catherine Morland) comes to a mansion that’s grown up around, yes, an antique abbey! Being an avid reader of Radcliffe and her fellows, Catherine expects Northanger to offer all the mysteries and “horrors” in which she vicariously delights. She goes as the friend (companion) of Eleanor Tilney, daughter of the Abbey’s owner. He, General Tilney, must therefore be the Moody Man. As a widower, he might legitimately be Catherine’s object, but she’s long preferred his son Henry, who is a young man not only of humor but also of good principles, so not a sleeve-secreter of daggers. The General makes for a good center of mysteries, however, such as what really happened to his wife, whom Catherine shiveringly deduces he didn’t love and therefore has imprisoned somewhere in the house. She looks for hidden documents (she finds some old laundry bills) and finally makes it to Mrs. Tilney’s once-bedroom in search of clues. There she’s discovered by Henry, who persuades her to temper her overactive imagination. Like Ness’s girl, when the mysteries are solved, Catherine “can let herself change. Let herself grow.” Not by sinking tendrils into the house, though. A rational Catherine is quite happy with Henry Tilney’s humble rectory. She lets Eleanor Tilney play the classic heroine by marrying her beloved, after he goes from rags to riches enough for the moody General.

Ness points out that the mid-20th-century Gothic romancers “drew pretty heavily on Charlotte Bronte’s Jane Eyre.” She’d like to think, though, that Jane eventually “conked Rochester hard over the head, and headed off to explore the world,” certainly a diversion from Gothic traditions. One midcentury novel plays brilliantly with those traditions, to literally divert into tragedy at its close. Or does it? That’s Shirley Jackson’s Haunting of Hill House.

Eleanor Vance is the youngish woman with an indifferent family and few friends who runs to a house of mysteries in search of sanctuary and the self she longs to be: one who belongs, who can be loved. Because such journeys always end in lovers’ meeting, Hill House must have a suitable male resident for her. Dr. Montague’s married, which leaves Luke (the house’s putative heir)—or in this case, a female resident, and Theodora is pretty much the moodiest of the three other ghosthunters. Or, wait, there’s also Hugh Crain, the original maker and master of Hill House. He makes a fine Gothic maybe-villain, nor should his being dead rule him out. Ghosts are Gothic-romantic, and if Eleanor winds up with anyone in the end, it’s with Hugh.

Except, here’s the atypical tragedy, she may only walk in isolated parallel with Hugh and the other ghosts of Hill House, since whatever walks there walks alone. On the other hand, she does become, if anything, a part of Hill House. The girl and the house, together forever, and maybe that’s Gothic romance at its purest!

Ruthanna’s Commentary

You can picture the cover now, can’t you? A woman in a diaphanous gown, running from a half-ruined mansion, hair wild in the moonlight… [Edited to add: I want it on record that I wrote this before seeing the Victoria Holt covers!]

So many possibilities lie behind that cover. And so many predictabilities as well: the gothic romance is a genre of plot, beats as surely integral as those of a mystery or romance. Ness’s deconstructive heroine is on some level aware of both possibility and predictability: it’s clear from the start that this is a girl who knows things, who has genre savvy and some level of agency over getting involved in this story. Gothic heroines have agency, but usually within deep constraints. They’re frequently stories about not getting to pick your role: about the bars of class and gender and economics, and about the danger of holding a liminal position where your enforced role has uncertain boundaries. Not ancient nobility like the brooding man, not clearly subservient like the cook and maids. But always, always, barred in by those who hold power.

Gothics are claustrophobic, even as they reveal that all roles carry uncertain boundaries and dangers. Houses that you must flee, but can’t get away from. Pasts and monsters and people that you must flee, but can’t get away from. The threat of being tossed out on the streets, and the threat of being locked up—and here, the temptation to lock yourself up, exchanging whatever freedom the world offers for the Wolfean de minimus room of one’s own. If nothing else it provides a door that locks, space that is yours alone, and a limit to the threats you must face.

If locked up, at least you might be fed. Given the time period, given the constraining roles available, this is far from a certainty elsewhere. Although what you eat, and whether you’re in any position to eat it, depend on what genre variant you’ve found yourself in. In a relatively mimetic gothic, you might simply be thought mad. But in Poe you might be in the liminal space between life and death; in Lovecraft the space between human and alien or human and eldritch horror.

Those not locked up, on the other hand, are likely to have gone a bit strange. Perhaps these eccentricities are caused by the house, or perhaps by their blood. Perhaps it has to be both: a gothic house, after all, is one with its family. When the House of Usher falls, it’s a disaster of both architecture and lineage. The rats in the walls are heralds of generational memory and trauma.

Part of claustrophobia is walls closing in, gradually reducing possibility, and that’s the shape of this story as well. The girl moves from metanarrative consideration of possible roles and possible lovers—get involved with another woman, and you might slip into another genre entirely—to specific results of those choices and ultimately to extremely specific, perhaps extremely well-planned, aftermaths. The hope of finding a room of her own first draws her to the house. In a gothic, the space is rarely your own—except that she will, ultimately, make it her own. Sort of.

In a traditional gothic, the relationship between girl and brooding man is overt, the relationship between girl and brooding house metaphorical. Here, it’s girl and house who come to a union merging both of their goals. She comes with the need to “coax out every secret, every ghost, every drop of blood.” And the house, in turn, wants everything revealed. It has its own agency and desires, like Hill House.

So was it her idea from the start, or does the house seduce her to put down literal roots? To sink tendrils into it like some not-so-metaphorical fungus? To become haunted, a monster who never has to worry again about being alone?

The best room of one’s own, perhaps, is the room one carries inside.

Next week, we celebrate our 450th post by watching some weird: Get Out, Jordan Peele’s 2017 directorial debut.

Ruthanna Emrys is the author of A Half-Built Garden and the Innsmouth Legacy series, including Winter Tide and Deep Roots. You can find some of her fiction, weird and otherwise, on Tor.com, most recently “The Word of Flesh and Soul.” Ruthanna is online on Twitter and Patreon and on Mastodon as r_emrys@wandering.shop, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her young adult Mythos novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.

Excellent analyses! For further conversation on this subject, see Jo Walton’s essay “A Girl And A House: The Gothic Novel”, https://www.tor.com/2009/09/24/anatomy-of-the-gothic/

I don’t have anything to add – I just thought this was a lot of fun. I do like to think that the woman walking away with the house in the end is the reader – forevermore caring story inside them.